By Barry Cottam

We field-naturalists tend to think the great outdoors and all its visible flora and fauna are pretty much where it’s at. We extend our vision with binoculars, spotting scopes, macro- and telephoto lenses. Often we’ll use a hand loupe to check out smaller items. But those of us who experienced Paul Hamilton’s whirlwind tour through the vast and intriguing world of microscopy will be forgiven for wanting something much stronger than a loupe.

The “real” world for the microscopist is one we cannot see with the naked eye. Most of us aren’t even aware of it; yet it’s a much more diverse and challenging place than the bigger world we usually occupy and one that deserves and rewards much more attention. Field and stereo microscopes might be the most useful to the field-naturalist, but Paul, a senior research assistant in the Museum of Nature’s algae lab in Gatineau, took us much deeper, introducing us to powerful instruments and techniques that enabled us to examine samples from the field – think pond water, slices of plant stem, minute insects – in exquisite detail.

As Paul reminded us throughout the event, “It’s all about playing with the light.”

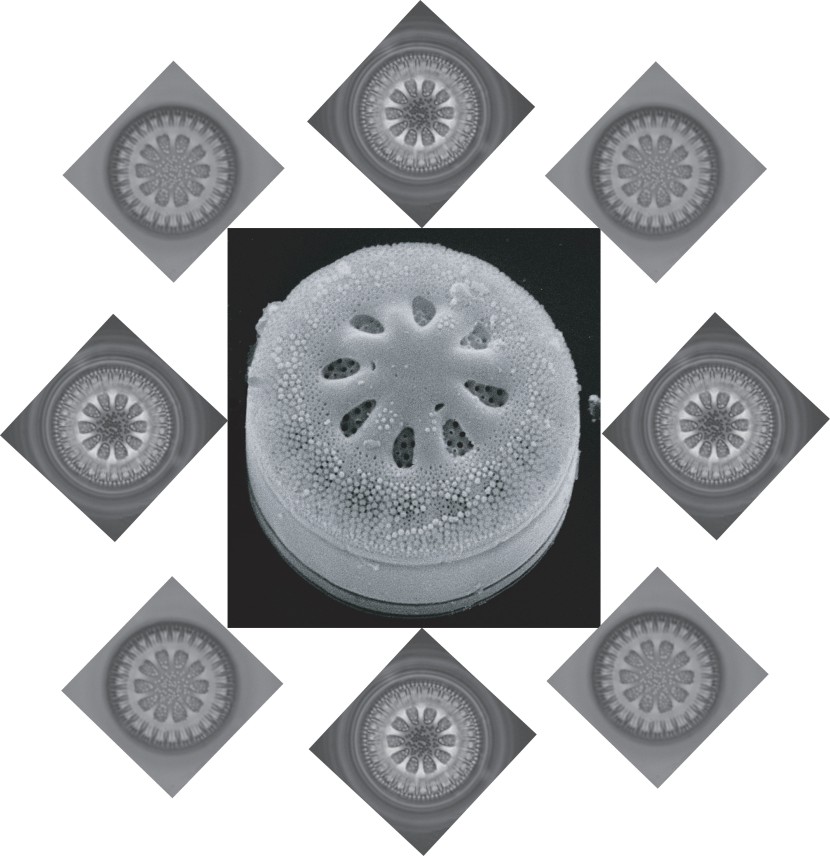

Examples of the kinds of images that can be made through the compound microscope and scanning electron microscope used in the workshop. This creature is Cyclotella antiqua, a freshwater diatom found in lakes and ponds in the Rockies and the Arctic.

The workshop alternated between hands-on sessions and PowerPoint presentations explaining lens optics, different types of eyepieces or oculars, and development of the various types of compound microscopes. Our small group – six signed up but colds kept two away – got to sample and compare each of these: white light (the normal view), dark field, phase contrast, differential interference contrast. (Two Nobel prizes have been awarded to scientists working out the difficult optics that make some of these possible.)

The workshop ended with our small group taking turns checking out diatoms on an electron microscope. Under a stereo microscope, these same diatoms show up in the dozens, while the more powerful compound scopes allow different views of a single diatom – the various techniques bringing out different aspects. But with the electron microscope, we were getting down to features not seen any other way.

In addition to allowing us ample viewing of many kinds of materials, Paul explained the basics of staining, slide preparation, and care of scopes, in particular the objective lenses – their most important and valuable single part.

Getting into microscopy can be expensive, but doesn’t have to be. Stereo scopes are relatively cheap, while compound scopes can cost between several hundred and several hundred thousand dollars. Electron microscopes are beyond the pocketbook of the hobbyist, running into a million or two for a new one. But older ones can sometimes be picked up for free. Hmmmm.