This is the first in a series of suggestions from the Conservation Committee for things you can do around your home in aid of wildlife and conservation. Some will be published in the next few issues of Trail & Landscape, but others will appear only as blog posts under the category “Conservation how to” – https://ofnc.wordpress.com/. They are all based on personal experience – ours and colleagues’. We would love to hear your thoughts about these practices and your experience with them – good or bad. And your suggestions for further good practices are very welcome.

by Fred Schueler

Figure 2: The brush pile by the goat yard, 4 and 6 St Lawrence Street, Bishops Mills, 19 November 2014. Notice spoiled eggs tossed onto the pile so they could decay out of the reach of dogs.

We got into making brush piles in the early 1980s when we were keeping Goats (Capra hircus), and feeding them, in part, on cut branches of White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis), Common Apple (Malus sylvestris), Manitoba Maple (Acer negundo), and European Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica). It occurred to us then that we were inadvertently following the advice of 1950s comic books for conservation, which advised constructing “brush piles for wildlife,” and showed these bursting with song and game birds, reptiles, and rabbits.

So the decades have rolled past, and our brush piles have waxed and waned depending on how many Goats and European Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) we’ve been feeding, and quite frankly the only “wildlife” that obviously seems to enjoy the brush piles are House Wrens (Troglodytes aedon). Riverbank Grapes (Vitis riparia), Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus), and Wild Cucumber (Echinocystis lobata) also enjoy the piles (an enjoyment we try to bias toward the grapes because of their edible leaves and fruit), and of course this vegetable enjoyment may conceal some use of the pile by vertebrates. Certainly Red Squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) scamper around in the vicinity of the piles and must take shelter there, and in some summers distinctively large American Toads (Anaxyrus americanus) have consistently been seen near a particular pile. In the winter, we see tracks of small mammals (Sorex, Blarina, Peromyscus, Microtus) leading to and from the piles, but it’s not certain whether there are more tracks near the piles than around lesser sites of cover.

Methods

Figure 1: Swedish or Sandvik brush axe has a blade as sharp as a knife with the weight of an axe behind it. Twenty-three years of experience has demonstrated this tool to be both very effective and amazingly safe for brush pilers, ages 3 to 67.

We cut invasive shrubs (mostly European Buckthorn and Scots Pine, Pinus sylvestris), cedar, and other species, with a brush axe (Figure 1) or pruning saw, offer them to the goats or rabbits to eat the leaves and twigs, put aside branches large enough to be useful as firewood, and then toss the remaining “brush” onto the pile. The pile also receives Glossy Buckthorn (Frangula alnus), which is unpalatable to the animals, and coarse herbaceous stems such as Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus), Common Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), and Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica).

Once the pile is more than 1.5 m tall, it can receive carcasses and food waste that you want to have decay out of the reach of ambient dogs, and any other organic waste not suitable for other composting arrangements. In seasons of rapid accretion, it’s helpful to “bash” the pile down periodically with a heavy log or pipe to keep it from getting too high. After a pile has been in place for a decade or so, you can move the persisting branches to another site, and cultivate the enriched friable soil for vegetables or install native plants suitable to the site.

Results

As of January 2016, the brush piles around our homesite are

- 2.3 m tall by 5 m in diameter at the edge of a Manitoba Maple grove (Figure 2, top of page)

- 7 m by 6 m by 1.4 m tall over an old foundation

- 3 m by 10 m and 1.5 m tall extending from an apple tree into a grassy area of old field

The piles convert what would otherwise be scattered branches into a compact pile, which doesn’t impede walking, lawn-mowing, or other human activities. After an earlier pile had been in place for a decade on another old foundation, we moved the persisting branches to be the basis of the first of these piles, and cultivated the enriched friable soil for squash and corn.

[Note: Brush piles can be any size. Please see the notes from other “pilers” below for descriptions of brush piles in other locations.]

Consequences

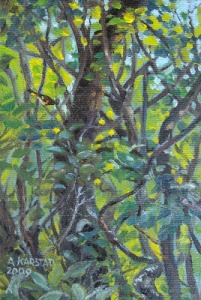

Figure 3: Thicket of Canada Plum trees painted by Aleta Karstad.

An elevated twiggy surface is different from the surroundings, and diversity of texture is bound to be good for biodiversity. It’s hard to imagine that this immense number of potential perches isn’t somehow “good for birds,” but also hard to imagine how much of an experimental setup it would take to show that it’s “better for birds” than surrounding Canada Plum (Prunus nigra) thickets (Figure 3). The twiggy surface can become a matrix for woody or herbaceous vines, which can include domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp.), morning glories (Convolvulus spp.), or trailing nasturtiums (Tropaeolum spp.), which can give a patina of cultivation, as well as providing culinary by-products.

With deeper, less dry soil, we could also plant Allegheny Vine (Adlumia fungosa) around some our shaded piles. “Organic waste not suitable for other composting arrangements” includes dog hair, which is deployed as nesting material for birds and more or less disappears, although we can’t tell how much is actually incorporated into nests.

A matrix of branchy shelter — It’s hard to see what’s going on within a brush pile, but mammals and toads must use it, and with the right combination of circumstances a pile can provide ideal basking sites and shelter for pregnant snakes. When we removed the pile from the old foundation, we found many shells of introduced Cepaea nemoralis snails, but not necessarily more than there would have been if the same area had just been left weedy, without the addition of the brush.

An area where directly rooted plants can’t grow — A brush pile can suppress stands of invasive alien plants, such as Goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria) and give vines a roothold.

An area where water from precipitation and nutrients and organic matter from decaying plant material can enter the soil directly — The brush pile provides an open soil texture for invertebrates to occupy, a different, more organic soil surface and texture, and it provides nutrients and water to both the surrounding vines and overarching trees. This more open soil texture and the trapping of snow and heat by the pile must also increase the range of species that can overwinter in an area. But what would it take for me to determine that half of our Grey Treefrogs (Hyla versicolor) hibernate in the brush piles?

Literature review

Googling about, one finds a page describing the construction of “brush piles for wildlife habitat” for just about every state and province, but these pages don’t seem to cite any research to back up the benefits claimed.

Sandy Garland found “a few more-scholarly references,” but the best of these, Sperry and Weatherhead,1 paralleled my experience: their 2009 “Internet search revealed that [many] U.S. state agencies… and numerous U.S. non-government agencies advise land owners to create brush piles to benefit wildlife… the creation of wildlife shelters, and a recommended approach for doing so is creating and retaining brush piles. Promotion of brush piles as a method for improving wildlife habitat is based on surprisingly little empirical evidence” (they found only three previous studies). They radio-tracked Texas Rat snakes (“Elaphe obsolete”) which “were found in brush piles 10% of the time, despite brush piles comprising less than 0.2% of the habitat by area,” and concluded that “more abundant small mammals and more moderate temperatures in brush piles than in surrounding habitats could explain snakes’ attraction to brush piles.”

A Wisconsin study2 of the use of brush piles by Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus) and Eastern Cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus) found that “Both snowshoe [hare]s and cottontails used our artificially constructed brush piles extensively: not only did tracks lead beneath many brush piles, but we occasionally flushed animals that had rested underneath them during the day. Despite this, we failed to detect a significant increase in over-winter survival associated with the presence of brush piles for either species… Coyotes [Canis latrans] may have hunted leporids so efficiently in dense vegetation, that even the close proximity of brush piles offered the leporids little benefit.”

If you search for brush piles in Google Scholar, you get hits on numerous articles on cottontail shelter, Northern Bobwhites (Colinus virginianus), Raccoons (Procyon lotor), snakes, mice, and lizards – but none from the latitude of Ontario.

If one consults the many “build a brush pile for wildlife” articles, they are extolled as “a great way to help your wild neighbours in need of dense cover, especially in areas where natural shelter has been removed for agriculture or urbanization,” but with no references to literature documenting these benefits. Some of the recommendations are to “Ensure a section of your brush pile gets direct sunlight and you will attract animals that like to bask… Add stone piles along the edges of the brush pile to act as basking sites… Encourage fruiting vines and flowering plants to add density and stability and attract pollinators and songbirds…. Add new brush to the top every few years to replace settled and decayed material, Cover the top with evergreen branches from your Christmas tree to provide a snow and ice barrier.” Also “Place it well away from your house to discourage wild tenants from moving in,” and, curiously, “Keep it away from standing dead trees, where raptors often scan for ground prey and launch their attacks,”3 although one could also create brush piles around snags to provide food to raptorial birds.

Going a bit south to fact sheets from the US, one learns that brush piles will attract chipmunks, weasels, turtles, lizards, towhees, wrens, flycatchers, dragonflies, salamanders, shrews, butterflies, rabbits, juncos, sparrows, toads, mice, ground beetles, skunks, snakes, quail, woodpeckers, and foxes.4

Maybe these great results are a result of starting the pile with a layer of logs or rocks, as recommended in the fact sheets. Maybe explicit use of brush piles is greater in warmer climates where there are more snakes and lizards? Maybe we need trail cameras and clever cover-object research to see how much our piles are being used? Or maybe those of us in “Chaos Corners,” for whom a brush pile is a form of neatness, are just unable to visualize the bio-deprived lives of those who “are reluctant to include a ‘messy’ pile of sticks in their gardens”? Basically, we think brush piles are cool, and we can see that they increase the diversity of habitat on our premises, so we’ll keep building them on a priori grounds.

References

- Sperry, J.H., and P.J. Weatherhead. 2010. Ratsnakes and brush piles: intended and unintended consequences of improving habitat for wildlife? American Midland Naturalist 163: 311–317.

- Cox, E.W., R.A. Garrott, and J.R. Cary. 1997. Effect of supplemental cover on survival of snowshoe hares and cottontail rabbits in patchy habitat. Canadian Journal of Zoology 75(9): 1357–1363.

- For example: Jhamandas, A. n.d. Build a brush pile for wildlife. Canadian Wildlife Federation, Ottawa, Canada.

- Munroe, K. n.d. Wildlife brush shelters – the missing piece of the habitat puzzle. National Wildlife Federation, Merrifield, Virginia, USA.

Brush piles in other locations

Iola Price writes

At McKay Lake, we’ve made brush piles 1.5–2 m high and 2–3 m diameter with buckthorn branches (from clearing these invasive shrubs). I have poked around in them and have yet to see any wildlife — not even spiders! Some piles have been there for 5 or more years and some of the larger trunks (up to 4.5 m long) have been in a pit for 2–10 years. Again, nothing much seems to be happening. A resident skunk is nearby, but prefers a site at the base of a tree, which she has dug out herself. The soil is landfill and really impoverished. I might find a few snail shells, but can’t recall a live one in a decade of digging in the soil there.

Our biggest success was in our own back yard, with a brush pile placed next to the chickadee/wren nesting box (about 1 m high and maybe 1.5 m long). After timing feeding intervals and number of trips to the pile, my husband reported that the wrens made great use of it. When the wrens failed to come back one year, I decided to use the space for something else and discovered at least one yellow jacket nest. Was that what the wrens were using to feed their young?

Figure 4: A brush pile at the Fletcher Wildlife Garden, Ottawa, created from branches of Ash (Fraxinus) killed by Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis). Photo from Sandra Garland.

Sandra Garland writes

Brush piles are an important part of a wildlife garden. They provide otherwise scarce shelter for small mammals, a place for squirrels to store food for winter, and an environment for insects and fungi to flourish. Most gardens need to be trimmed and groomed periodically, so gardeners also have an ongoing source of material to build a brush pile. Unfortunately, many people are reluctant to include a “messy” pile of sticks in their gardens. Here are a few tips to make brush piles fit in:

- Position your brush pile near the back of your garden bed, perhaps between shrubs or near the base of a tree.

- When building the pile, start with some large branches laid parallel, then another row at right angles. This makes spaces for small animals.

- As you add smaller branches, insert them base first into the existing pile. The result will be considerably tidier than if you just toss branches on top of each other.

- Every fall, add a layer of leaves, on and around the pile.

- Every spring, add the stems and branches that you cut back from the plants in your garden.

If you view your brush pile as a work of art rather than debris, you can make it a key part of your garden, while helping wildlife and the environment.

Christine Hanrahan writes

It does seem that most people suggest building brush piles on top of a layer of logs or rocks. I have never done this. At the Fletcher Wildlife Garden (FWG), the brush piles I’ve built over the years have been just a big pile of branches. Eventually, the pile gets smaller and smaller as it decomposes. Over the years I have seen flocks of White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis) ducking into the piles when disturbed. I’ve seen the same behaviour with Song Sparrows (Melospiza melodia). I’ve seen rabbits going into them when dogs are nearby, and ditto for squirrels. I’ve also seen red squirrels storing pine cones and other food in brush piles, as well as burrowing into the brush piles. I’ve seen singles of various bird species, mostly ground feeders, using brush piles, either to perch on or, often, to scurry into.

Naomi Langlois-Anderson writes

Our yard is about 4 acres, severed from a former 200-acre farm. About six years ago, the barn on our property burned to the ground, leaving a cement floor. Seeds found crevices in which to sprout, and so dense clumps of Scotch Thistle (Cirsium vulgare), Lamb’s-quarters (Chenopodium album), Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), and a few other types of plants grew to large proportions here and there on the concrete pad. As our yard has several mature limb-dropping varieties of trees — Large-toothed Aspen (Populus grandidentata), Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum), Weeping Willow (Salix babylonica), and Manitoba Maple — we often have quite a bit of brush to gather in the spring. The old cement barn pad became the most convenient location to store this brush.

I presume there are some rodents hiding there, as my cat would sometimes sit near the brush piles, looking interested at what’s inside. I have noticed that lots of birds come to pick through the dried seeds from the weedy plants that grow there. They are mostly Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) and House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), but other varieties do some quick forages in the piles as well. We have a pair of Eastern Phoebes (Sayornis phoebe) that nest over our door and I have seen them sitting on the brush pile.

Dan Brunton’s variation

Brush piles can be very helpful around a winter bird feeder – even in urban areas. The benefit of protection from predators (including domestic cats) and easy access to the food is immediately evident. Here’s a dramatic photo proving just that. Taken this week at our feeder, it show “only” 13 of the 16 Northern Cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) that were at and about the feeder at one time. Prior to the artificial thicket being put in place a few weeks earlier, it would be unusual to see more than two cardinals around the feeder at one time. The thicket is also frequently employed for sheltering and safer approach to the feeder by Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis), chickadees, Eastern Cottontails, and even an over-wintering White-throated Sparrow.